Redesigning Death Care

An Interview with Katrina Spade

What happens to our bodies after we die? Most of us are either cremated or conventionally buried in a cemetery. Katrina Spade, the founder and director of the Urban Death Project, says that both of these options are wasteful and “ensure that the very last thing that most of us will do on this earth is poison it.” She has designed a new eco-friendly option, called recomposition, based on the process of composting. In addition to providing a more sustainable option in the death care industry, Spade envisions creating recomposition centers that are more socially and economically equitable than our current funeral homes.

Spade recently spoke with the Garrison Institute about the environmental consequences of our current death care practices, the importance of ritual at the end of life, and her belief that we live better lives when we’re conscious of death.

You’ve been working on a new option for how we lay our loved ones to rest. What’s wrong with our current funeral industry?

The two most available options ensure that the very last thing that most of us will do on this earth is poison it. Conventional burial typically involves embalming, a casket, a concrete grave liner, and then, of course, a cemetery. Another option is cremation, which is rising in popularity very quickly because people think it’s more ecological—but it actually isn’t. There are pretty significant carbon dioxide emissions with cremation and it destroys whatever potential we have left in us for new growth when we die.

Are there any eco-friendly funeral options for people currently?

Each of the options I just mentioned are chosen by 48% and 49% of Americans today, but there is a smattering of people who are buried in natural burial grounds. A natural burial is where you’re buried in a shroud instead of a casket. You’re not embalmed and most of the time you’re buried just a few feet down in the ground. Often, it’s conservation land that’s used as the burial site, and microbes and bacteria and plant life help the body decompose. Natural burials are a beautiful option and they’ve always been an inspiration for me. But they’re really more appropriate for the rural setting.

When I began this work, I was looking at our huge urban population—50% of the world’s population now lives in cities—and thinking about what a large number of bodies that is to care for. Natural burial has never been scalable to that level.

Katrina Spade, founder and director of the Urban Death Project

So you started to work on the Urban Death Project.

The thing that I’ve designed, which we are now calling recomposition, is based on principles of mortality composting that has been studied for decades with livestock on farms and at research institutions. A few decades ago, (after the cottage industry of livestock rendering went away), if a farmer had a couple hundred cattle and three of them died for some reason (and couldn’t eat them), they would have trouble disposing of their livestock carcasses. So all this research went into finding the very simple method of covering an animal carcass with high carbon material—which is mulch, animal bedding, and usually some manure in there to get it nice and hot—and, in about six to nine months, the animal would have decomposed, including most of the bones. After that, you have compost that can be re-used on the fields and crops. This is something that’s been well researched and has been happening for decades now.

I found out about that process and a light bulb went off. My task since then has been to take that principle and create a system that’s both appropriate for our urban centers and supports the grieving process. I want it to feel supportive to the human experience of death.

Is your primary concern about the existing funeral industry that it isn’t environmentally friendly?

In my mind our funeral industry is failing us on three fronts: environmentally, socially and economically. Environmentally, we’re absolutely failing. Both cremation and burial pollute the air so that the last thing many of us do is toxic for the earth. Another problem with our current system is that many people don’t find meaning in conventional burial or cremation. Those options are the default options and we go with them because they’re easy, not because they’re meaningful. And, economically, the current funeral industry is purely for-profit—a $20 billion industry—and it relies on our denial of death in that people choose the default options because they don’t want to think about it.

This is not to say that every funeral home or funeral director takes advantage of people, but the lack of transparency around death care and the funeral industry goes hand in hand with people being taken advantage of.

So recomposition at the Urban Death Project is not an expensive option?

We’re still working out the details of the cost, but our goal is to have it be less than the cost of a cremation with a funeral. We will have a sliding scale fee and a community fund that supports those that can’t pay for services. Caring for the whole community is an integral part of our mission. So, we’re a non-profit organization whose mission is to care for people after they die, and we’re creating a culture of giving that supports a whole community around this issue. The end-of-life is so rich and death care for our loved ones can be so full of meaning when it’s done right. It’s easy to imagine creating a culture of giving around death care.

Earlier you mentioned a lack of meaning around current funeral practices and in your TEDx Talk you say that “ritual matters.” Can you say more about how this project supports ritual in a way that current practices don’t?

I started this work by thinking about the built environment what kind of spaces we have, (or don’t have), that support us as grieving people and as people who know we’re going to die someday. Cemeteries can be beautiful but for many people they feel antiquated and, from an urban planning standpoint, you can’t really access them easily like, say, a public park. They’re more like private grounds that you can go in for the day, but you’re mostly not allowed to have a picnic there.

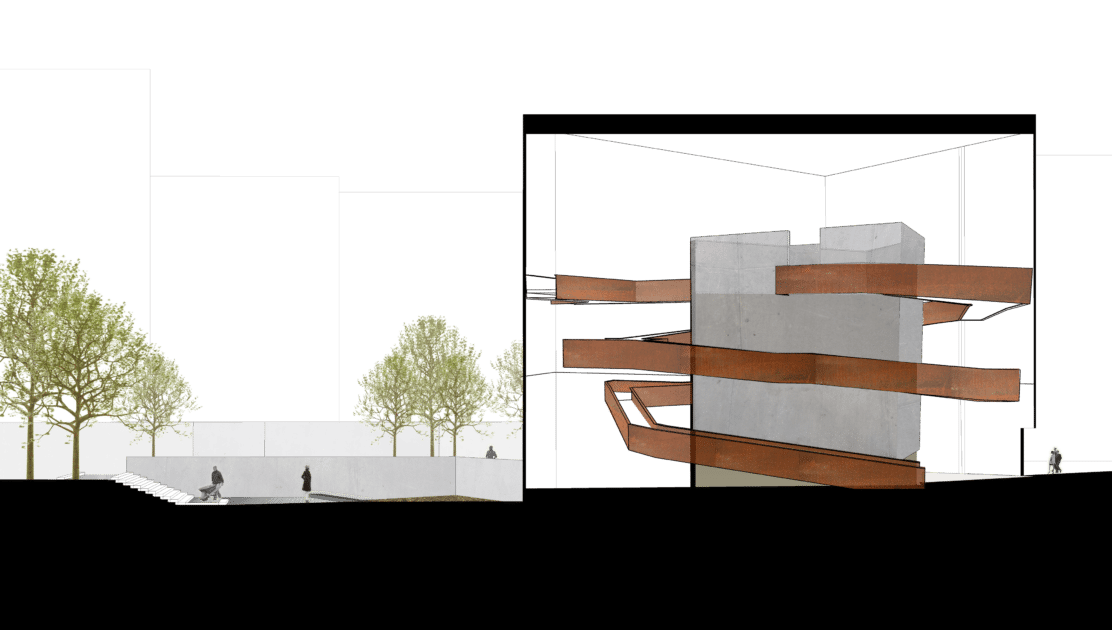

Crematories are mostly in the industrial zones of cities, and they are rarely designed to support families taking part in the work of death care. Then you have funeral homes, which by and large are kind of dowdy, uninviting places. This isn’t true of all of them, but it is true of many. So when I started thinking about what meaningful death care would look like from a built environment standpoint, my first thought was that we should be more involved, not less, in the process of death care. So I started by designing a building in the middle of our cities that would support the grieving as they cared for their loved ones. This is a place that has the kind of staff and space that allows friends and families to take on as much of the process as they can. For example, a shrouding room with staff to support friends and family as they wash and prepare the body for disposition.

Friends and Family Carry the Body to the Top of the Core

And, at the same time, I was designing this system that would literally transform bodies into soil. That system is vertically stacked, due to necessity of land use and consideration of the urban environment. It’s about three stories tall—we can call it the recomposition core—and it’s like a big room extruded vertically. The necessity of creating a vertical system led to the realization that somebody needs to get the body of the deceased to the top of the system because bodies are laid into wood chips at the top and over time, through natural decomposition, they’re moved downwards and are extracted below as soil.

So we thought that friends and family could be able to carry the dead up around this recomposition core, three stories, on ramps to the top. That becomes the framework for the ritual. It’s very simple: friends and family wash and shroud the body, and then they carry it to the top of this core. To me, that’s very beautiful. The living are using their own energy to carry this body up to the top, and when they lay it into this recomposition core, a new energy starts to be created in the form of compost.

It’s easy to imagine friends and family not wanting to—or not being able to—wash the body.

It’s absolutely true. The goal is to have staff that is specially trained to encourage families and friends to do as much as they want and can do, and that’s going to look very different from family to family. But you might have, say, a mother who died and a son who does not feel up to touching the body, but wants to be in the room when someone is preparing the body for recomposition. You might also have a situation where families who think they are not able to participate might actually find themselves doing so. This isn’t to push people to do something that they’re uncomfortable with, but to give them the opportunity. They will have the opportunity to have zero contact all the way through to doing everything for this person who they love.

Is there a way to memorialize a death at one of these centers? One thing that can be meaningful at cemeteries is that people have a place to go afterwards to honor their loved ones.

There are a couple of ways to memorialize with recomposition in this system. Every recomposition center will be a place of memorial because there’ll be gardens onsite. In the long-term vision, each one in every neighborhood is designed differently for the community that it’s in, but they all have gardens and those gardens are nourished directly from the compost or soil created.

I think it would depend on the designer and community a little bit whether there would be actual plaques because the idea is for this to be an almost infinite system where, as we die, we’re folded back into the city that we love by turning into soil, and that soil nourishes plant life. So if you started putting plaques up, maybe they should decompose too. I don’t know. Or maybe the plaques would have a 50-year life or something because theoretically you’d get full with plaques.

We’re also going to be encouraging friends and families to take some of that soil and bring it home and grow a rose garden or grove of trees. Take it to a place in the wild that feels meaningful. It’s almost like a hybrid of a cemetery and what you do with ashes when someone’s cremated.

How has working on this project helped—or not helped—you when thinking about your own death?

I think my family was a little more open and comfortable talking about death than many. My parents were both in medicine and they had patients who died, which they didn’t keep from us. Since doing this project, I have spoken to many people who tell me about losing someone they loved. So there was a deep dive into this emotional space really quickly with people I’d never met before. But I got used to that, and it’s actually now just beautiful and not hard for me emotionally. I cry with people on a weekly basis because they tell me about their experience on the deathbed or with losing a loved one, and it’s just been a beautiful experience.

In general, I do think that we live better lives when we are conscious of our own impending doom. This work has made me so grateful to be alive. I still fear death, but not because of the event so much, but because I don’t want to leave this life yet. I’m not afraid of dying, but I’m not ready. But sometimes I think about the fact that children are so good with the idea that life includes death and renewal. If you talk to a young child about the cycle of life and death, they get it. That must mean there’s something right about it, you know?

Images courtesy of the Urban Death Project