Resilience Fatigue

An Interview with Denese Shervington

Most of the time when we talk about resilience, we talk about bouncing back from acute traumatic events, like medical emergencies or natural disasters. We don’t always acknowledge the resilience necessary to respond to chronic adversities and structural inequities that lead to historical trauma through multiple generations. Psychiatrist and public health advocate Denese Shervington—who directs a community-based post-disaster mental health recovery division that she created in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina—believes that, in order to effectively address the stress of acute trauma, we need to recognize the long-lasting effects of historical trauma.

Dr. Shervington is the President and CEO of The Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies (IWES), a community-based translational public health institute in New Orleans. We spoke with her recently about expanding the term resilience to include historical trauma, how trauma shows up in the body, and pathways to build individual and community resilience.

What is the social understanding of “resilience” in the black communities you serve? Does the concept resonate? Or does it create resentment and resistance?

As a socially defined racial group, African Americans hold what Chamberlin Carlson describes as “a unique historical position in the context of American society shaped by the legacy of slavery.” Hence, any concept of resilience that does not contextualize the long history of racial inequities and ongoing structural violence becomes a challenging one. As was recently stated by an African American expert on resilience, “After you have pounded a prize fighter to the floor several times, at some point his legs are going to be broken and he can’t get back up.” Without an analysis of the impact of chronic adversities on the management of acute shocks, the construct of resilience will continue to create resistance and resentment within the black community.

You suggest that our current common understanding of “resilience” is centered around bouncing back from immediate disturbances and disruptions—Hurricane Katrina is the example you use—and not structural inequities with deep roots or the chronic adversities you were just speaking of. Can you say more about this?

Structural inequities create individual and collective trauma, eventually damaging the capacity of communities and the people who inhabit them people to be efficacious and resilient during acute shocks. Such vulnerable populations usually have the greater disaster risk, are generally impacted to a greater extent and for longer periods, and are at greater risk during the recovery period for reinforcement of pre-existing inequities. As was noted by the Prevention Institute, chronic trauma and adversity eventually wears and tears down the built environment, the socio-cultural environment—such as social networks, trust, social norms, and capacity for advocacy—and the economic environment. It is well documented that the rescue and recovery efforts post Katrina did not factor in one of the most devastating and nefarious outcomes of structural inequities—poverty. So, for example, evacuation plans did not include providing transportation for those with no access to private transportation, what was approximately 30% of the population. Nor did they provide decent housing support and shelters for those unable to leave the city.

How do you think we can improve the concept of resilience to include “bouncing back” from historical trauma?

Creating a more resilient community for people who have experienced historical trauma requires a trauma-informed approach to community rebuilding and revitalizing. It starts with acknowledging the traumatic injuries and then providing services at the individual, community, and systems levels that address and ameliorate the harm. As was stated in the framework for addressing health inequities put forth by the New Orleans Health Department:

The history and lingering effects of slavery, segregation, and trauma from Hurricane Katrina have shaped the health of the mostly black and poor residents of New Orleans. We must acknowledge the long-lasting effects of this history and work to eliminate bias and inequities in institutions and systems that have an impact on the well being of our communities. To advance equity, government and other institutions must be willing to examine policies and practices that may perpetuate inequities and limit access to opportunities such as quality education, stable employment, affordable housing and access to healthy foods and recreational spaces.

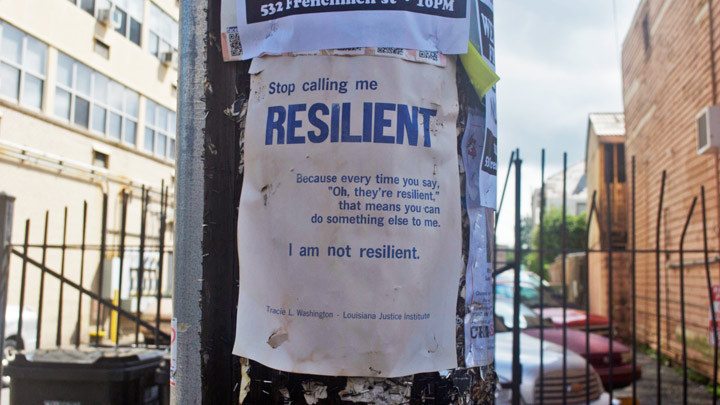

An “I am not resilient” sign on a New Orleans street post.

Let’s talk about how trauma shows up in the body. Can you explain the concept of “allostatic load”? And, while you’re at it, can you also explain “weathering” and its long-term consequences for individuals and families in low-income communities?

Allostasis means “stability through change.” The cells of our body are constantly and actively adapting to a changing and stressful environment so as to support the systems essential to life and create health. Excessive wear and tear on the body from prolonged and excessive stressors—both psychosocial and environmental—result in allostatic load, which manifests as the loss of adaptive plasticity and resilience. The primary mediators of allostasis are the adrenal “stress” hormones, neurotransmitters, and immune cytokines. Surplus of these substances from excessive activation can lead to stress-related disorders such as anxiety disorders, depression, metabolic syndromes, cardiac diseases, infection, and violence.

Weathering refers to the deterioration in reproductive health status over the childbearing years among African-American women, which has contributed to the long standing racial disparity in the rates of adverse birth outcomes. Weathering is due to socio-economic cumulative disadvantage, in particular the duration of exposure to low-income, under-resourced communities.

Your work draws on the new science of epigenetics, which shows that the trauma of racism from previous generations shows up in the genetic material of blacks today. Can you say more about this?

Behavioral epigenetic research—which studies the relationship between the environment, genes, and health—has shown that present traumas, or that of ancestors, can influence how genetic material gets expressed. Applying epigentic science to descendants of the African slave trade, for example, could shed light on how oppression “gets under our skin” and impacts our physical and mental health. Some scholars have been concerned, however, about epigenetics being coopted for eugenic purposes. The eugenic argument—put forward in the 19th century about the need for racial improvement through better breeding—was used “as a technique of normalization that divides humans into the biologically superior (normal) and the inferior (abnormal).” To the extent that epigenetics redefines difference as epigenetic damage it could serve as molecular confirmation of deviance. As was put forth by Becky Mansfield and Julie Guthman, if epigenetics “is about how racism and disadvantage get under the skin, it normalizes white bodies and behaviors and reinforces the idea that people of color need to emulate the environments and behaviors of rich white people in order to protect themselves and their offspring.”

Hence, the subject of epigenetics and race must be approached with caution. Dorothy Roberts JD, a well-known legal scholar and activist, cautioned, “It is when scientists and doctors insist that their use of race is purely biological that we should be most wary.”

How do we know that genetic differences are due to racism in previous generations and not the racism of today?

Epigenetics reflects the molecular environment prenatally of the mother and her ancestors. It also reflects the post-natal attachment and touching behaviours of the primary caretaker. And also in future births, as Becky Mansfield and Julie Guthman argue, “epigenetic outcomes of exposure in one’s own lifetime become a factor for future generations—whether through direct inheritance or the social environment.” The well-known researcher in the field, Moshe Szyf, referred to epigenetics as “long-term memory of past exposures.”

Denese Shervington

So far we’ve mostly discussed the challenges you strive to overcome in your work. What are pathways to individual and community resilience?

A good place to start is with the recognition of the manifestation of community trauma on the socio-cultural environment, the built environment, and the economic environment. Then we can put policies in place to address them. Some put forth by the Prevention Institute include reclaiming public space to be appealing to residents and reflective of their culture, rebuilding and maintaining public spaces that encourage positive social interactions and relationships, as well as healthy behaviors and activities, and improving economic opportunities for youth and adults.

There are a few lessons we could learn from how the Australian government managed the 2009 bush fires in Victoria. Their guiding principle was the definition of “recovery” set forth by Daniel Alesch and others in which recovery was viewed as a self-organizing process in which the “community repairs or develops social, political, and economic processes, institutions, and relationships that enable it to function in the new context within which it finds itself.” As such it was recognized that vulnerable people are generally impacted to a greater extent and for a longer period, that responding to disaster without recognizing vulnerabilities can further reinforce pre-existing social inequality, and that new vulnerabilities can be created by the relief and recovery process. This provided the framework that was recommended: Build community capacity so that they can have the resilience to lead their own recovery, and then work with community as they are in the best position to identify local needs and priorities. Connect with established community networks to support long-term capacity and organize the public sector to address specific recovery needs that harness expertise and complement local participation. Then plan, review, assess, and respond to changing community priorities because recovery is non-linear with no clear end-point.

What’s the role of culture in building community resilience?

Culture is learned behavior that transmits a group’s survival arsenal through shared norms, beliefs, customs, and creative expressions. Positive communal norms can be used to capitalize upon the collective power of individuals striving to cope with stress and chronic adversities—it can send positive messages to the community, and promote optimism and hope. Intentionally creating opportunities for social interaction and cultural expressions help to dislodge deeply held reactions to traumatic events, such as fear and sadness. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, it was love of the city’s culture that brought New Orleanians back home in spite of the difficulties of living in a place that suffered immense destruction and offered little recovery support for communities of color. Being in New Orleans’ culture helped many people to regain identity and orientation back in their city. Cultural expressions through local music and dance helped to facilitate emotional release and realignment, directing people how to celebrate life and respect death.

Sam Mowe is the Garrison Institute’s Editor in Chief.