A Brief History of Life

Natural selection equipped us with human brains that presuppose the specialness of the self, which can lead to hatred of others. Mindfulness meditation can help.

By Robert WrightFor four billion years, life on this planet has been ascending to higher and higher levels of organization. First there were just bare, self-replicating strands of information; then they encased themselves in cells; then some of these cells got together and formed multicellular organisms; then some of those organisms developed complex brains, and some species of brainy organisms became highly social. One species of social, brainy organism was so social and brainy that it launched a whole second kind of evolution: cultural evolution, the evolution of ideas and customs and technologies. And this second kind of evolution carried this species to higher and higher levels of social organization—from hunter-gatherer village to ancient state to empire and so on, until here we are, on the brink of establishing a cohesive global society. As if to underscore what a natural outgrowth of biological and cultural evolution this is, there is even a kind of emerging global brain—the internet, animated by the human brains that form its neurons.

If you saw all this from outer space and in time lapse, so that billions of years were compressed into minutes, it might seem like you were watching the growth and maturation of a single planetary organism. Indeed, this growth might seem driven by such powerful developmental logic that the continued congealing of that organism—that is, the emergence of a peaceful and orderly global civilization—was inevitable.

You’d be wrong about the inevitable part—that’s the whole problem—but it’s true that the logic behind the process has been powerful. For starters, natural selection is so wildly inventive that the advent of a species smart enough to launch cultural evolution was probably pretty likely all along. The subsequent expansion of our species’ social organization, from hunter-gatherer village all the way to globalization, was also likely, because cultural evolution, like biological evolution, has a powerful creative engine behind it.

You’d be wrong about the inevitable part—that’s the whole problem—but it’s true that the logic behind the process has been powerful. For starters, natural selection is so wildly inventive that the advent of a species smart enough to launch cultural evolution was probably pretty likely all along. The subsequent expansion of our species’ social organization, from hunter-gatherer village all the way to globalization, was also likely, because cultural evolution, like biological evolution, has a powerful creative engine behind it.

At least, that’s the case I made in a book called Nonzero. I argued that, ever since the Stone Age, the expansion of human social organization has been impelled by a technologically driven growth in the range of interdependence. Over time, people at farther and farther distances from one another have come into contact and in many cases have come to trade or otherwise cooperate with each other. Today, more than ever, we depend on people halfway around the world for the goods and services that sustain us, as do those people. In other words, the fates of people around the world have become more and more correlated. That’s what interdependence is.

And, oddly, this correlation is actually strengthened by such global problems as climate change, problems that are bad for people in diverse parts of the world and whose solution would therefore be good for people in diverse parts of the world. In various different senses, people on different continents are in the same boat. It is in our common interest to work together. What could go wrong?

Well, if you’re viewing the whole thing up close, answers may spring to mind. Here’s the answer that springs to my mind: groups of people fighting with each other. The lines of battle may be ethnic, religious, national, or ideological, but antagonism seems to have grown along many of these lines in recent years. What’s more, there seem to be some dangerous positive feedback loops: antagonism on one side creates more antagonism on the other, which creates more antagonism on the first side, and so on. This is the kind of dynamic that can fuel a long downward spiral—which would be alarming even if we weren’t living in an age of nuclear weapons and increasingly lethal and accessible biological weapons. But we are living in such an age.

What’s more, we’re living in an age when information technologies make it easy for relatively small numbers of people bound by a common enmity to find each other, no matter where on earth they are, and then coordinate to deploy violence. Hatred, even when diffuse and far-flung, has increasingly lethal potential.

What causes all the hatred? At some level, it’s always the same thing: human beings operating under the influence of human brains whose design presupposed their specialness. That is, human beings operating under the influence of the reality-distortion fields that control us in many and subtle ways, convincing us that we and ours are in the right, that we are by nature good, and that, when we do the occasional bad thing, it’s not a reflection of the “real us”; whereas they and theirs aren’t in the right and aren’t by nature good, and when they do the occasional good thing, it’s not a reflection of the “real them.” And it doesn’t help matters that these reality-distortion fields often magnify, even out-and-out fabricate, the threat posed by them and theirs.

So, yes, we need to reject the core evolutionary value of the specialness of self. Indeed, there’s probably never been a time in human history when this rejection was more vital. But we don’t want to reject what is also in a sense a value of natural selection’s: that the creation and sustenance of sentient life is good. Happily, mindfulness meditation is well suited to fighting that first value while serving the second one. As a bonus, it brings us closer to the truth.

You could even view mindfulness meditation itself as in some sense a part of the natural unfolding of life, part of the ongoing co-evolutionary process. Maybe, given the constraints under which this universe operates, the only way for complex consciousness to arise on this planet was for it to be warped in the process, distorted by the exaltation of self. And maybe, once social organization approaches the global level, the only way for complex consciousness to flourish on this planet—or even to survive—is for it to now be unwarped, or at least partly unwarped.

We can thank Buddhism for laying out a path to this unwarping. Buddhism isn’t alone in deserving thanks. Thinkers in many religious and philosophical traditions, from ancient times onward, have in some sense seen the problem and have suggested ways of addressing it—which is good, because it means that many traditions have resources to draw on as humankind confronts its collective challenge. But Buddhism deserves credit for so early, so acutely, and so systematically diagnosing the problem and for offering such a comprehensive prescription. And now, finally, science has corroborated the diagnosis and revealed its roots: the problem was built into us by our creator, natural selection. Fortunately, natural selection also equipped us with the tools for addressing the problem—rational and reflective faculties that in principle can transcend the circumstances of their birth. And, who knows, maybe they will.

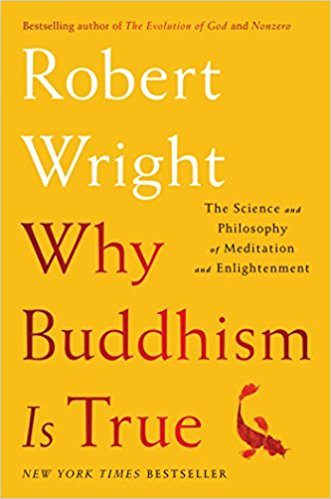

Robert Wright is the New York Times bestselling author of The Evolution of God (a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize), Nonzero, The Moral Animal, Three Scientists and their Gods (a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award), and Why Buddhism Is True. He is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of the widely respected Bloggingheads.tv and MeaningofLife.tv. He has written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New York Times, Time, Slate, and The New Republic. He has taught at the University of Pennsylvania and at Princeton University, where he also created the popular online course “Buddhism and Modern Psychology.” He is currently Visiting Professor of Science and Religion at Union Theological Seminary in New York.

This article is from Why Buddhism Is True by Robert Wright. Copyright © 2017 by Robert Wright. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Read an interview with Robert Wright about Why Buddhism is True.

Photo courtesy of Ethan Weil on Unsplash

Spot on. Love everything about this line of thinking and the views on evolution, civilization and our current predicament. Going to add some of Mr. Wright’s books to my reading list. Thanks.