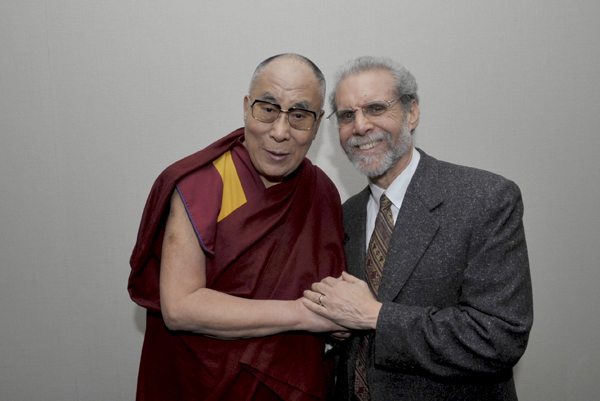

A Force for Good: An Interview with Daniel Goleman

Journalist Daniel Goleman is the author of many books, including the international bestseller Emotional Intelligence and Destructive Emotions: A Scientific Dialogue with the Dalai Lama. His latest book, A Force for Good: The Dalai Lama’s Vision for Our World, is another collaboration with His Holiness, in which Goleman outlines the Dalai Lama’s theory of change and his vision for the future.

What are the broad strokes of the future that the Dalai Lama is imagining?

In order to make a better world, the Dalai Lama encourages us to first manage our own destructive emotions better. That way we don’t operate from anger or rage or frustration or fear, but rather we can be calmer and clearer, and therefore more skillful.

Then, he says, adopt a moral rudder of compassion—genuine concern for everyone—and then act. It’s not enough just to espouse compassion and to meditate on it. You have to act on it for it to be real. He outlines a number of ways each of us could act: in terms of honesty in the public sphere; cleaning up corruption and collusion; having a more humane economic system; helping those in need, but not just by charity, but, wherever possible helping them live better and take care of themselves with dignity; heal the earth. He says our earth is our only home, and our home is on fire, and we have to really analyze the links between human activity and the degradation of the systems that support life.

It helps, he says, to take a long view. When we take the long view we realize that, over the centuries, things are actually getting better. We need to keep this in mind as we act.

Yes, in the book you describe the Dalai Lama as a “futurist,” which I thought was an interesting description for an 80-year-old, Tibetan religious leader.

He just thinks over centuries, and he thinks far into the future. It really has expanded my sense of the future that I can have any impact on. He’s more and more interested, he told me, in reaching Millennials and younger generations. He’s less interested in spending time giving, say, Buddhist teachings to the same faces, the same older faces, and more and more interested in meeting with students wherever he goes. Because, he says, these are the people of the 21st century. These are the people in whose hands the future will be shaped. He thinks like a futurist, and he acts that way, too. His whole message is about what can happen in the centuries ahead.

So the first step in that big vision is working with our own destructive emotions. What are the primary strategies or methods that he recommends for doing this?

So the first step in that big vision is working with our own destructive emotions. What are the primary strategies or methods that he recommends for doing this?

He doesn’t dictate how we should do this. In all parts of the vision, he only tells us what the goal is. But, like a good parent or a good boss, he doesn’t micromanage. He is not prescribing, for example, meditation. A Force For Good is not a Buddhist book or a Buddhist vision. This is a vision for all of humanity. And he says each of us can find our own methods. It might be psychotherapy for someone. It might be mindfulness for someone else. It might be a very positive, parenting kind of remedial relationship. It could be any number of things. But the metric for progress is how often we find ourselves in the grip of our most disturbing emotions, versus how well we manage them and can put them aside or recover from them.

Paul Ekman, the psychologist, once told me that the definition of maturity is widening the gap between impulse and action. And I think that’s another good measure.

Something we do at the Garrison Institute is explore the relationship between personal transformation and systems transformation. After your conversations with the Dalai Lama, what insights do you have on that?

Well, I think this is implicit in the Dalai Lama’s vision, because he starts at the personal level. He says, transform yourself so that you’re a better tool for transforming the system. His vision of compassion and action is very much the individual acting to change the system in surprisingly assertive ways. For example, when he talks about cleaning up the public sphere, he’s saying, we need to be transparent. Bringing transparency and accountability to business, to politics, to religion, to science. You could say sports, given the recent FIFA scandals. Otherwise, he says, these systems just are not fair. Some people are gaming other people, and we have to stop that. Corruption and collusion is like a cancer. And so he sees that operating at the systems level but from an inner space that is as clear and calm and energized and effective as we can be.

But what about all the ways in which systems make individual change really difficult? Is it even possible to always transcend the system in which you find yourself embedded?

I think our Dalai Lama is pretty much a pragmatist. He says, do whatever you can do, given your constraints and given your possibilities. You might be someone who can talk to other people, who can put a message out on social media, who can mobilize a smaller or a larger group in order to raise awareness by changing a policy or law. You might have access to someone in Congress, and you might be able to persuade them to change a law.

So although we might easily get discouraged, thinking, well, what difference does it make what I do? The growing importance of big data analytics, which looks at each one of us as an aggregate, makes whatever each one of us does quite important.

There’s also the point, for example, when it comes to sustainability, that if any one of us changes a habit over the rest of our lives, particularly when we’re young, for the better, for sustainability, it actually adds up to large, large numbers. So those are two dimensions in which an individual change, which you might dismiss as irrelevant, actually has big impact.