Death Asks Us to Live Authentically

Mindfulness of our mortality helps us investigate our priorities.

By Josh KordaDeath is inevitable. And may arrive even sooner than we dread. A truth is revealed in the precariousness of the human condition, in the body’s vulnerability to infection, disease, and injury: mortality is not the result of fortune or a world gone awry, but a consequence of life itself. While it has been established that we are living in the safest era our species has known, a long life is never guaranteed. While we make assumptions about our safety and life expectancy, and we eat bran and install fire alarms in the hopes of bettering our odds for longevity, our existence is only a blood clot or viral infection away from extinction.

How we relate to this certainty determines how authentic, meaningful, and purposeful our lives are. The more we deny the inevitability of death, the more we will make decisions that are shallow and incomplete. Think of how painful it will be when we’re confronted with imminent death—in an accident, or when a disease is diagnosed—and we realize that we have traded far too much for apparent emotional or financial security.

We can’t truly understand this truth using rational thought, in part because that same rational thought helped us to justify so many bad choices; rational thought tells us that the job we hate pays the mortgage or the partner we don’t love is a good person who’s nice to our friends. This truth reveals itself by raw experience: We must experience loss.

Mindfulness of Death

While contemplating our own mortality can seem to be a downer at best and downright depressing at worst, reflecting on it is a terrific way to investigate our priorities and routines.

When I decide whether or not to take on a project, if I don’t weigh the commitment against my time limitations, given the certainty of death, I make the choice without fully considering the real implications. I have only so much time left; is this job, or relationship, or life circumstance, really how I want to spend it? Every significant choice we make should, in one way or another, be evaluated against the Buddha’s first noble truth of life: the inevitabilities of old age, sickness, death, and separation from the loved.

When I decide whether or not to take on a project, if I don’t weigh the commitment against my time limitations, given the certainty of death, I make the choice without fully considering the real implications. I have only so much time left; is this job, or relationship, or life circumstance, really how I want to spend it? Every significant choice we make should, in one way or another, be evaluated against the Buddha’s first noble truth of life: the inevitabilities of old age, sickness, death, and separation from the loved.

Thinking about death also puts resentment and bitterness in perspective. It helps us practice forgiveness and have compassion for the mistakes of others because we realize that time is short. We can relieve ourselves of the resentment and bitterness that we carry through life as so much inner chatter, stress, and hostility. In letting go of resentment, we also acknowledge that we have made mistakes for which we must forgive ourselves, if we are to live free of shame and remorse.

Reflecting on the inevitability of death and the fragility of life doesn’t mean that we will choose a lifestyle of hedonistic, immediate gratification. More likely, we will consider the real value of our time spent. We might take the time to find more invigorating employment or cut down our work hours, or it might simply change the way we relate to our responsibilities exactly as they are. We may become more attentive to our loved ones or spend more evenings with friends. The understanding of death opens up new possibilities for life, rather than keeping me plodding along the same path, day in and out, hemmed in by ingrained routines and misguided beliefs.

Death provides the most truthful perspective on how to live. When it comes time to die, we’ll care more about what we’ve done for others and what contributions we’ve made than we will about how much money we have. We want to look back and see an authentic and meaningful life.

The certainty and unpredictability of death sheds light on life’s meaning and priorities. So why wouldn’t you spend a lot of time thinking about it? Because our denial of death allows us to remain deluded, preoccupied, and distracted by unfulfilling bullshit. Living any day as if we’ve been guaranteed countless more lies at the heart of our delusion and out-of-whack priorities. The natural tendency to ignore our mortality is a tool we use to get through another day without meaning. Our refusal to acknowledge our imminent death is also an obstacle to staying present and connecting to our reality at this moment. For this reason, spending a whole life living in the denial of death would be both tragic and dishonorable.

Practice: Mindfulness of Death

What does a meditation on death in spiritual practice look like? We might sit quietly for a while, keeping our breath in mind until our attention settles on the physical sensations of inhalation and exhalation in the abdomen or chest, or the sensations of air entering and exiting the tip of the nostrils or mouth. When we’re focused, we might slowly, silently repeat a simple thought: “One day this body will stop breathing” or “This breath could be my last.”

As we add these reflections, note how the words affect how we attend to the sensations of the breath. We observe how these simple truths, when kept in mind, influence how we perceive our experience. Then we shift our attention to our external senses of sight and hearing: “One day the world will blur as my eyesight fails; the sounds will fade with the loss of my hearing; memories will vanish into remote areas of the mind; all the skills I take for granted will evaporate.”

Finally, we might bring to mind the five daily recollections of the Dharma: “I am of the nature to grow old, to become sick, and to die; I will be separated from all that is dear to me; all I really own are the actions I take.”

After repeating the five recollections, we might purposely bring to mind our life’s dramas—the lingering resentments toward family members, friends, or foes; looming financial bills; or mounting responsibilities—and ask ourselves, when framed by the inevitable, how much do these really matter? Knowing that I will be separated from all I cherish and hold dear, are these little dramas really so critical?

We may find that these recollections change the way we greet the frustrations, setbacks, and travails of life; they may well fade in significance when one’s final moments are visualized. Perhaps we will be proud, from this perspective, of the choices we’ve made, or perhaps some decisions won’t fare well under such scrutiny. As all of life moves deathward, we can at least transform our greatest sadness—that we know we must die—into our greatest source of wisdom.

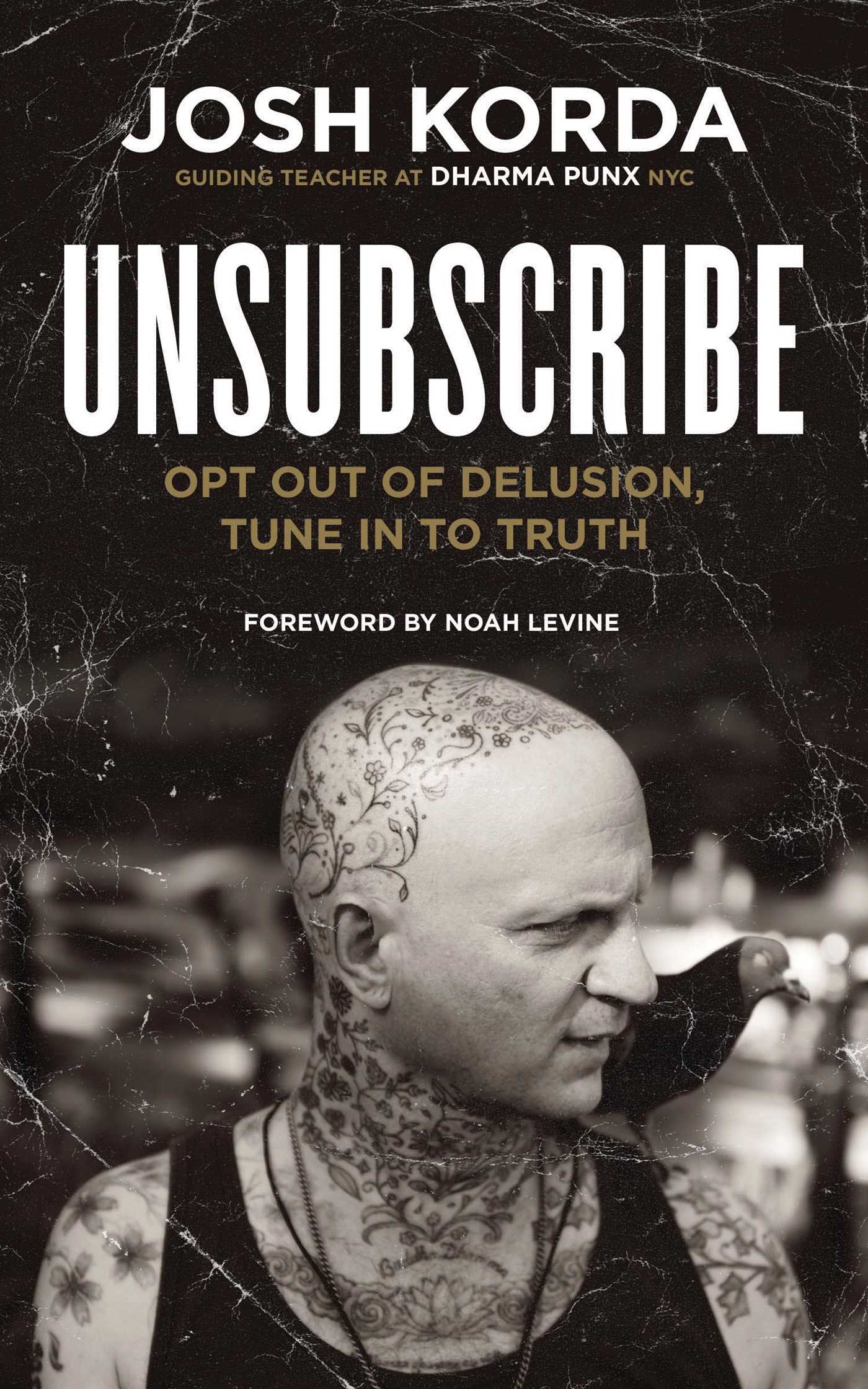

Josh Korda has been the guiding teacher at New York Dharma Punx NYC since 2005 and he teaches frequently at the Garrison Institute. His first book, Unsubscribe: Opt Out of Delusion, Tune In to Truth, from which this article is adapted with permission of Wisdom Publications, will be published in November 2017.

Photo courtesy of Mathew MacQuarrie on Unsplash