Satisfy Your Craving for Human Contact

The inadequacy of digital connection has left us yearning for the felt presence of other people.

By Tracy Dennis-TiwaryOur love affair with digital is over.

It seems like forever, but it’s been only 10 years since the iPhone first seduced us. Can we remember a time when we didn’t have the sleek, delicious feel of a device in the palm of our hand and instant gratification at our fingertips?

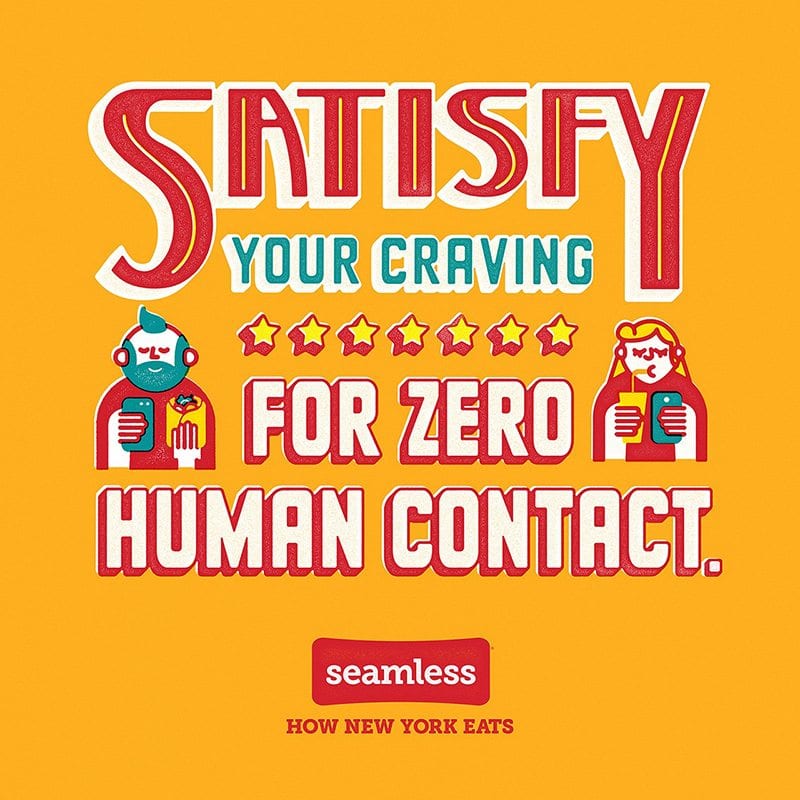

Can we remember a time when “app” wasn’t even a word, when we didn’t care how many “likes” we had, and when we might have questioned an advertising campaign that encourages us to have “zero human contact”?

Now the pendulum has swung back and we are starting to sense the price we might be paying when we cut ourselves off from human contact in favor of the speed and efficiency of digital technology. Increasingly, evidence shows that this price includes the erosion of our mental and physical health, the dominance of trolls and fake news, and the surveillance-economy monetization of our every tap and key stroke by technology monopolies like Facebook and Google.

The pendulum has also swung back because we realize that we are looking at screens more than human faces and that we are starved for real conversation and connection. The fact is we have woken up to the knowledge that humans evolved to be social, and that text on screens and likes posted on Facebook are only pitiful shadows cast on the wall by the fire of real human presence. Day by day, click by click, our social selves are slowly being starved.

Science confirms these instincts by showing that the presence of a supportive loved one lowers levels of the stress hormone cortisol and raises levels of oxytocin, a social bonding hormone. Taking this as a starting point in 2012, Seth Pollak, Leslie Seltzer, and colleagues published a study that tested whether these same powerful biological effects emerge when a teenage girl who has gone through a stressor seeks support from her mother through instant messaging. They found that unlike teens interacting with their mothers in person or over the phone, those who IM’d showed little to no release of oxytocin and showed cortisol levels as high as those who received no support. Connection through digital devices just isn’t the same as the comforting voice or presence of a mom.

While this research study and others show the inadequacy of digital connection, the story of one person’s deeply human experience of grief further illustrates the necessity of physical presence for emotional healing. Maneesh Juneja is a digital health futurist and health data analytics expert. After his beloved sister passed away unexpectedly, he discovered that it was only face-to-face human connection that helped him cope with his grief. Indeed, although his life revolved around digital technology, technology was the last thing he turned to for coping with his loss. A VR hang out at a “backyard BBQ” left him feeling disconnected and worse than before; but he sought out the “human checkout counter” at the local grocery store rather than the much faster and more efficient self-checkout machine option just for the brief experience of human contact. He realized that he yearned for human presence over technological convenience, and that human presence—touch, eye contact, and voice—was uniquely healing.

Where does this leave us?

One thing we can do is remember and rediscover the joys of analog. In his book The Revenge of Analog and his recent NYT Opinion piece, David Sax writes that the “walled garden of analog saves both time and inspires creativity.” He champions “obsolete” analog technologies, arguing that whether turntables, books, or pen and paper, these more cumbersome and sometimes costly analog options are worth it because they engage all our senses and are uniquely suited for cultivating connection and conversations. To get a stronger sense of your community and neighborhood, take time to visit those “brick and mortar” stores to interact with your favorite Italian grocer (mine is Vinny) or book geek who always gives you the best recommendations. And we can question whether a MOOC (massive open online course) could ever inspire us and change our lives the way a single teacher in the classroom can.

Another answer to the question of where this leaves us is that we now have more wisdom than we started with ten years ago. Unlike the binary logic we’ve come to admire, many of us now know that it’s not an all or nothing choice. We might decide to turn off our devices more often— to choose settings that staunch the flow of disruptive beeps, rings, and notifications—so that our time with ourselves and others is not constantly interrupted. We might choose to have dinner with our families without devices in reach. We might pay attention to how time on our phone seems to have a direct and causal impact on our levels of stress and anxiety, We might notice how the never ending email inbox leaves us exhausted or that the tidal pull of needing to “document the moment” through digital photos blocks us from savoring the actual experience.

These observations lead to choices we can make—and that we can help our children make—on a daily basis. We might even decide to walk down the sidewalk without clutching a device, following a GPS, or constantly checking our weather app. We might just enjoy the awe we feel when we immerse ourselves in a beautiful sunny day and revel in not knowing whether it will be quite as sunny a day tomorrow.

Dr. Tracy Dennis-Tiwary, PhD is an emotion scientist and Professor in the Psychology Department at Hunter College of the City University of New York, where she is also co-director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Health Technology and Wellness and of the Stress, Anxiety, and Resilience Research Center. She is the creator of the stress-reduction app Personal Zen. You can read more about her work at dennis-tiwary.com.

Header image courtesy of unsplash.com.