Climate Change for Aliens

(And We Are the Aliens)

By Tom AndersenAdam Frank is an oddsmaker on the grandest scale. Thirty years ago, he says, science did not even know that planets existed outside the Solar System. But a revolution in data and observations has changed that. In a big way. We now know, he says, that not only are there other planets but that a few of them, like Earth, are located in habitable zones in relation to the stars they revolve around – “Goldilocks Zone worlds,” not too cold and not too hot.

How many? Ten billion trillion.

Adam is an astrophysicist at the University of Rochester and the author of a new book, The Light of the Stars: Alien Worlds and the Fate of the Earth. He argues that with so many planets, the odds are overwhelming that many of them have seen civilizations come and go. Those civilizations would necessarily have had to trigger climate change – it’s a consequence of civilization. Some of those civilizations would have been done in by it. But others would have managed it and survived it.

Adam gave a fascinating talk based on The Light of the Stars at the Garrison Institute’s Pathways to Planetary Health symposium on April 17-19, 2018. To keep the discussion going, we’ve been posting follow-up conversations on Lineages with some of the participants – Andrew Revkin and Carl Safina, Vincent Stanley and John Fullerton, Jonathan F.P. Rose and Tom Lovejoy, and now Adam Frank. Adam spoke last week with Tom Andersen.

He started by describing The Light of the Stars.

Adam Frank: The book is essentially an attempt to reframe how we think about what is happening to us right now, vis-à-vis climate change and the Anthropocene. The central thesis is that when it comes to climate change, we’re telling the wrong story.

Adam Frank: The book is essentially an attempt to reframe how we think about what is happening to us right now, vis-à-vis climate change and the Anthropocene. The central thesis is that when it comes to climate change, we’re telling the wrong story.

We basically have two stories about climate change. One is it’s not happening at all, and that’s not very effective. And the other one is, “We suck” – you know, that human beings are a greedy plague on the planet. My thesis is that if you take the astrobiological perspective, if you take the 10,000-light-year view of what’s happening to us, you end up with a very, very different story that has a very different set of imperatives and outlooks on what’s happening to us and what we should be focusing on.

It’s climate change for aliens, where we are the aliens. The attempt is to look at climate change as a generic phenomenon that will happen to any species, on any planet that grows a technological civilization.

Tom Andersen: One of the points you make is that you have ample data to conclude that the overwhelming odds are that it has happened in the past, and not just once.

Adam Frank: It’s important to understand, when we think about the possibility for other civilizations on other planets, that we didn’t even know 30 years ago whether there were any other planets [outside our solar system]. When I was coming up in astronomy, the existence of other planets was still an entirely open question. It may have been that our solar system was a freak, that we had a star and a bunch of worlds orbiting it.

Now this is an important question because we don’t think you can get life without planets. I mean, maybe something goes on that we totally don’t understand. But in general, it would really seem like planets are a prerequisite for life. So the question is, how many planets are out there that are in the right place for life to form?

We now know that pretty much every star has a planet orbiting around it. And if you count up five stars that you see in the sky, one of them has a planet in just the right place—meaning not too warm and not too cold—for liquid water to exist, which means life could exist there.

So if you now add up all the planets in the right place over the history of the universe, you end up with 10 billion trillion habitable-zone worlds, or what we call Goldilocks Zone worlds. And every one of those constitutes an experiment that the universe has run in evolution and the possibility of life, and then intelligence, and then civilizations forming.

So unless the universe is perversely biased against it, and every one of those 10 billion trillion experiments failed, we’re not the first time. It’s happened before. Right? Nature has had 10 billion trillion chances to get what’s happened here happening somewhere else.

With those kinds of numbers —and those are firm numbers—it’s really up to the pessimists to explain how it could be that we’re the only time over the course of cosmic history that a civilization has evolved.

Tom Andersen: And in this context of climate change, why is that significant?

Adam Frank: A planet is basically nature’s way of taking sunlight and doing something interesting with it, right? So as long as you have an atmosphere, then interesting things are going to happen on your planet. Even without life. Now, if you have life, you get the possibility of even more interesting things happening. We have studied Mars, we’ve studied Venus, we’ve studied Titan, which is a moon that has an atmosphere, we’ve studied the gas giants, and we’ve studied Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history.

All of this you put together, and we now understand pretty well how planets work. And the conclusion is that if you get a planet that has life on it, and that biosphere develops intelligence and civilization, you can’t help but trigger climate change. You can think of a civilization as a machine for harvesting energy and doing work with it. Irrigation, building buildings, laying down roads. Whatever the civilization wants to do, it has to harvest energy from the planet to do it. Climate change is going to be an inevitable consequence of civilization building.

Tom Andersen: What should we take away from that lesson?

Adam Frank: A new way of thinking about what’s happening to us. As I said, we have two stories. One is that it’s not happening, and two is that we suck. From this perspective, now you end up with a new story.

The first part is that the question – whether humans are responsible for climate change – disappears. Because if you look at the politics of climate change, we have spent most of the last 30 years in this ridiculous argument about did we or didn’t we change the climate. From this perspective, it’s not even a question. Of course you changed the climate. What else did you expect? You built a world-girdling civilization, and the only possible consequence is to change the climate.

So from this perspective, the fundamental political debate disappears. And that’s the most important thing that happens in a paradigm shift. The old questions become unimportant or meaningless.

But let’s keep expanding this new story. So the first part is that of course you changed the climate. And that changes what we think our relationship to the biosphere is. From this new perspective, civilization and everything we’re building is no less natural than a forest. A city is just as much a natural consequence of the biosphere’s innovative activity as an old-growth forest is.

So our relationship to the biosphere shifts with this new perspective. And our sense of what we’re doing changes. Because now what we see is that triggering climate change was not our fault, in a very specific sense. It was not intentional. I always like to say, it’s not like we discovered fossil fuels and immediately said to ourselves, “Let’s destroy the planet! Let’s use this stuff to wreak havoc on ecosystems!”

By discovering fossil fuels, we were doing what we had always done, which was find power sources for civilization. It used to be running water. It used to be animal dung. It used to be animals themselves. So this narrative of, “We’re a plague on the planet, we’re destroying the planet,” is both unhelpful and fundamentally wrong.

And from this new perspective, you lose this burden of guilt that is actually numbing. I think. It actually blunts action. It also plays into the hands of your enemies. Because the climate denialists love the tree-hugging, “trees are more important than humans.” So both of those two fundamental stories disappear under this new story that we get from the astrobiological perspective.

One of the things I like to do, just to sort of be shocking, is to say we should be proud of triggering climate change. Because what it means is that as a species, our capacity has risen to the point where we were able to change the atmosphere of an entire planet, which is not bad for a bunch of hairless monkeys.

And likewise, you can use this when some climate denier is arguing about, like, “We couldn’t have changed the planet!”

You can say, “Well, why do you hate human beings so much? Why are you so against human beings? Human beings have done this amazing thing in our industrial capacity. Why do you think we’re so incapable and impotent?” Which often throws them for a loop.

And as this book came out and I’ve been talking with a lot of people, I find this to be extremely useful. People who normally I never would have been able to reach have come up to me and been like, “Wow. I’m a Republican. I think of myself as being on the right. But you’re the first person who’s ever given me a perspective on climate change that I don’t feel like I have to push against.”

Tom Andersen: Do you worry that they will take that conclusion and say, “Aren’t we great? Climate change is a natural thing. We don’t need to do anything about it”?

Adam Frank: No. No. Because if they walk away with that, then they weren’t listening. Just because triggering our climate change wasn’t intentional, it doesn’t mean that now that climate change is here, that there is not an urgent responsibility to do something about it. The story starts with, “Triggering it wasn’t our fault.” The story ends with, “Not doing something about it will be our folly.” We won’t survive if we don’t do something about it. Because that’s the astrobiological perspective. There have probably been many civilizations. They all have triggered climate change. Some of them figure out how to make the changes that you need to make, and some of them don’t.

So it’s all about, are you going to end up in the pile of losers, in the dustbin of cosmic history? Or do you get to be one of the winners that makes it through and develops — and this is the important point—some kind of cooperative relationship with the biosphere?

Tom Andersen: So we should be encouraged that some of them have made it through, even though obviously we’re never going to know what it was that they did to make it through.

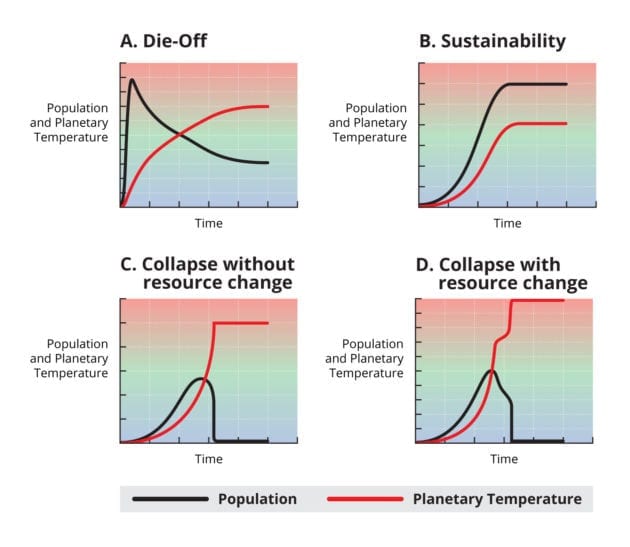

Adam Frank: No, actually. That’s part of the research that I’ve done. We modeled the interaction between a civilization and a planet, to ask the question, “Can anybody make it through?”

Of course these models were very simplified, and it was a first step. But what we actually found was there were trajectories that led to a nice equilibria. Your population rose. The planet changed, but it didn’t change so much that everybody died. And that was a really encouraging thing. There were also trajectories where everybody died. There were collapse trajectories as well.

That’s the answer to the right-leaning person who’s open to this discussion. Now you have to decide whether or not you’re going to be a winner or a loser.

Tom Andersen: Do the models provide any reason not to move quickly?

Adam Frank: No. Those models all say you need to take action. Those models all say that it’s a dangerous transition. When I talk about thinking about climate change in a different way, what we recognize from this perspective is that climate change is not a problem to solve. It is a dangerous transition that has to be navigated.

Tom Andersen: Near the close of your talk at Garrison, you discussed the things we hold sacred.

Adam Frank: Part of that comes from Jared Diamond’s book, Collapse. He’s looking at these different societies that collapsed or didn’t collapse. And he says one of the things that really determined whether or not a civilization made it through its difficult transitions was the ability to shift its values. And I think that’s exactly what we’re going through. That’s a good description of what we have to do. We have to change what we value. And the most important thing, I think, about climate change is that it forces a species—us, now, in this case—to put itself back into the biosphere. To re-identify itself with life writ large.

The shifts in the value are really shifts to deep ecology. The only way we’re going to make it through is if we come to some cooperative relationship with the biosphere. We’re not above it, stepping on it, bending it to our will. But instead we have to understand kind of deeply how it works, and align ourselves with that.

Tom Andersen: So this is like the astrobiological version of saying we’re all one with nature.

Adam Frank: Absolutely. Exactly. Yeah. Somebody might snicker at that, but that’s where we’re headed. And what a surprise, right? What a surprise that there would be something deeply spiritual at the root of this dilemma.

Tom Andersen: Bottom line, optimistic or pessimistic?

Adam Frank explains during his talk at our recent Pathways to Planetary Health symposium (“Sustainability and the Astro-biological Perspective: Framing Human Futures in a Planetary Context”) why deep ecological values are needed where compassion and an identification with life become the primary values.

Adam Frank: I’m by nature optimistic, because, really, what’s the alternative? [laughs] You know? Human beings are remarkably resilient and innovative. But I by no means think that it’s an absolute. When I put on my astronomer hat, it’s like, “Hey, there’s a lot of worlds out there. There’s a lot of experiments being run. There’s absolutely no guarantee that we’re going to make it.”

But I have faith in us. I have faith that we’re going to figure it out—and part of the reason is I teach, and the students I teach, they’re ready. We just need to get out of their damn way and let them solve these problems.

Tom Andersen, author of This Fine Piece of Water: An Environmental History of Long Island Sound, conducted the interview.