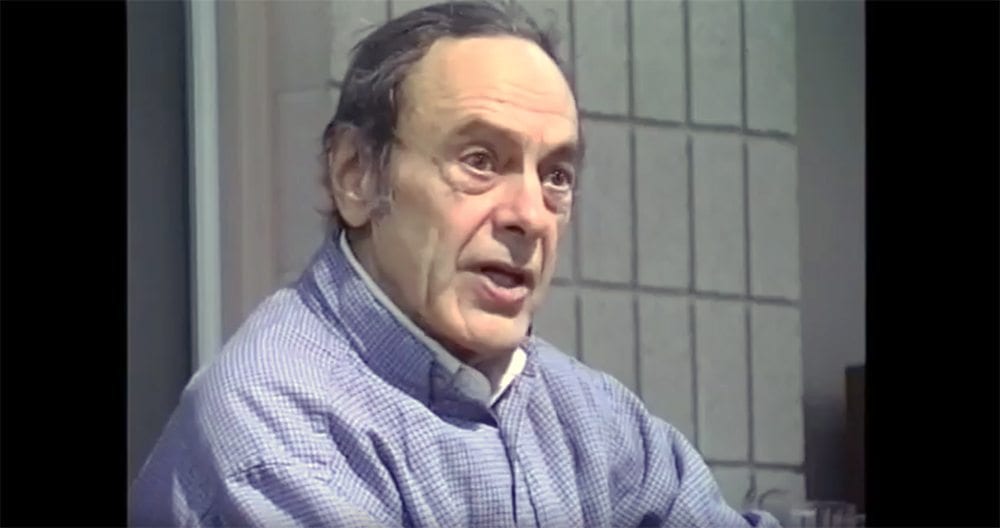

Remembering Eugene Gendlin

The groundbreaking philosopher and psychologist who gave the world the practice called Focusing died on May 1, 2017.

By David RomeEugene Gendlin—the groundbreaking philosopher and psychologist who gave the world the practice called Focusing—died on May 1 of this year at the age of 90. He passed away peacefully, attended to by close students, at his home in Rockland County, New York, just across the Hudson River from the Garrison Institute. Focusing, also referred to as “felt-sensing,” is a practice of allowing our bodies to guide us to deeper self-knowledge and healing; it is also a powerful antidote to oppression and hate in these chaotic times.

Gendlin was born in Vienna in 1926 and lived there until the age of 11, when the Nazi takeover of 1938 made it mortally dangerous to be a Jew in Austria. Together with his parents he narrowly escaped, first to Holland and then to the United States. His early experience of Nazi totalitarianism deeply affected his thinking and his unyielding opposition to any form of power over other people. He was also deeply affected by the many decisions his father made on the basis of deep intuitive feelings—felt senses, as Gendlin later termed them—by which he navigated the family’s escape amidst the chaos and confusion of their extreme circumstances.

Gendlin’s work is exceptional in the way it bridges the fields of philosophy and psychology, as well as bridging serious academic work to usable techniques for personal development. While a student of philosophy at the University of Chicago in the 1950s, he became a disciple and then colleague of the great American psychologist Carl Rogers, who was revolutionizing the theory and practice of psychotherapy with his “person-centered” approach. Under Rogers’ guidance, and drawing on his deep grasp of European phenomenology, Gendlin demonstrated that the key ingredient necessary for a successful therapy outcome was the client’s pre-existing capacity for accessing a bodily-felt experience of the issues they were struggling with.

Some clients entered into psychotherapy with this innate capacity, while others did not. The breakthrough came when Gendlin realized that this ability to locate a pre-conceptual, somatic kind of knowing was a trainable skill. He developed a simple six-step practice for finding “felt senses,” as he called them, and drawing on them for deep intuitive insights and fresh, life-affirming action steps.

In 1978 Gendlin published this new approach to personal growth in his book Focusing, which went on to sell more than half a million copies in 18 languages. The name “Focusing’” is rather misleading, having little to do with the conventional idea of focused attention. Rather Gendlin chose it as a metaphor for the process of recognizing vague, subtle, or ephemeral somatic sensations that could gradually be brought into focus, as one might adjust a pair of binoculars to turn a blurry visual image into clear, recognizable objects.

Once a felt sense has come into focus—meaning it is more present, clear, and stable—one can move to the step Gendlin calls “asking.” Simple questions like “What are you worried about?” or “What do you need?” are addressed to the felt sense itself, as if talking with a friend. Often (not always) if one waits patiently and gently, the felt sense will answer with an unexpected insight, an “Aha!” moment, along with a body sense of release or opening. Something held deep inside has come unstuck, providing a new sense of direction and fresh energy to undertake it.

My own discovery of Focusing, coming after almost three decades of Buddhist meditation practice and study, was a revelation. It gave me a way of bringing buried feelings and unrecognized assumptions to light and allowed me to contemplate them in a bodily-felt way that fostered palpable changes in habitual patterns, freeing me for a fuller realization of my potential. These days, more and more meditators and mindfulness practitioners are discovering the deep contemplative resonance of Focusing practice and its ability to open new avenues of self-knowledge and personal development.

I first met Gendlin himself—Gene, as everyone called him—in the late 1990s when he was teaching a method he called Thinking at the Edge (TAE). While rooted in Focusing, TAE differs in not being oriented toward personal growth; instead, by generating novel logical concepts directly from one’s own unique lived experience, it allows individuals to contribute fresh understandings to the world at large. (TAE derived from a course he taught in theory construction at the University of Chicago for many years.)

Not long after meeting Gene, I was invited by Gene’s wife, Mary Hendricks Gendlin, then executive director of the Focusing Institute, to join the Institute’s board of directors. This afforded me the opportunity to get to know Gene and his extraordinary mind and heart more intimately and led to a series of visits to his apartment-office on the west side of Manhattan for far-reaching, one-on-one conversations. Gene’s huge yet humble generosity in giving of his time and attention to seekers like myself is testified to by many individuals who were so blessed.

In 2005, while I was serving on the Focusing Institute’s board, I joined the staff of the Garrison Institute, allowing me to bring the two organizations together in a fruitful collaboration. Focusing programs have been a mainstay in Garrison’s calendar for many years. Living so nearby, Gene spoke many times at Garrison, especially during the annual Focusing Institute Summer School program. Video recordings of a number of these fascinating talks are available through the Focusing Institute bookstore.

Here is a quote from a 2007 talk at the Garrison Institute that embodies the depth, subtlety, and frequently koan-like qualities of Gendlin’s teaching. He is encouraging Focusing trainers to be very painstaking and precise in the way in which they present the practice: “I would like you to be very specific when you teach, and at the same time I need you to be pleased that other people are being very specific in a very different way!”

Gendlin’s profound intellectual and practice legacy is being carried forward by the Focusing Institute, recently renamed the International Focusing Institute, which serves as a communications and information-sharing hub for the worldwide Focusing movement. And Focusing is truly an international phenomenon, with active and growing communities of practitioners all over the world learning, teaching, and further developing Focusing in a multitude of cultures and languages.

Recently the Focusing Institute announced the formation of the Eugene Gendlin Center for Research in Experiential Philosophy and Psychology to carry forward his unique “Philosophy of the Implicit” and stimulate research validating the effectiveness of Focusing in bringing about real and deep change for individuals—and, by extension, groups, organizations, and human society altogether. Later this year Northwestern University press will publish two new books by Gendlin, his philosophical masterwork A Process Model and Saying What We Mean, a collection of seminal articles and essays.

I have been changed by Eugene Gendlin’s brilliant, compassionate work. It has enriched my own work, my relationships, and my inner life, along with my understanding and practice of Buddhism. May it offer similar gifts to many more people, and to our perilous world, as time goes on.

David Rome is the author of Your Body Knows the Answer: Using Your Felt Sense to Solve Problems, Effect Change, and Liberate Creativity, about Mindful Focusing, his own integration of Gendlin’s Focusing with Buddhist mindfulness-awareness practices.

On September 22-24, Rome will be co-leading a retreat at the Garrison Institute with Hope Martin, “Embodied Listening: Uncovering Our Bodies’ Natural Wisdom.”

Image: YouTube