Who’s Listening?

Andrew Forsthoefel on the gift of being deeply listened to during an eleven-month walk across the United States.

By Andrew ForsthoefelWhere would you find yourself if your need to be right and your addiction to certainty dissolved into a willingness to listen? Who would you be, then? And who would we be together—as a country, as a planet—if each one of us actually knew what listening was and how to do it because we had, over the course of our lives, been deeply listened to? This kind of listening does have to be learned and that is the only way to learn it: to receive it.

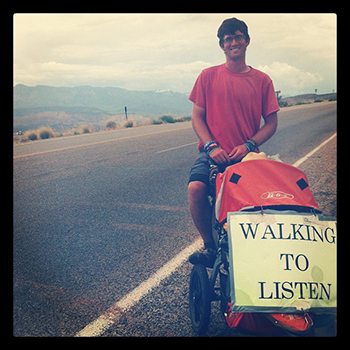

I received the gift of being deeply listened to over an eleven-month walk across the United States. It was 2011 and I was a new college graduate. I’d walked out my backdoor near Philadelphia with a sign on my pack that read “Walking to Listen.” I didn’t know who I was or where to go with my life, and rather than pretend otherwise, I decided I’d dive straight into the eye of the storm of my uncertainty. I was going to make myself vulnerable, by walking on the highways far from everything I knew and everyone I loved, and by asking questions that would reveal the fact that I didn’t know the answers to these important questions—which was, in a way, an expression of my interdependence. I wanted to test the edges of that interdependence—see how much I could do on my own, discover where I couldn’t continue on alone. And so I set out, intending to give the very thing I ended up receiving from hundreds of Americans—the sense of belonging that comes from being deeply seen and heard.

Andrew Forsthoefel

A 4,000-mile journey began with 10,000 uncertainties. How was I going to survive the cold of the upcoming winter, and the heat of a summer in the desert? How would my body do, walking 20 miles a day, sometimes more? Where would I sleep? What would I eat? How would I endure the solitude? And what about all the people?

I was terrified to step into the uncertainty because I had been trained to avoid it at all costs. We celebrate the certain in America. In a large swath of our cultural paradigm, you are to know the answers to questions, or to at least pretend that you know. You are to have solutions to problems. You are to armor yourself with convictions, because you are frail or fallible if you risk the undefended nakedness it takes to wonder and listen, reveal and behold. In this paradigm, “I don’t know” is a humiliating admission of failure, rather than a gateway into revelation and transformation. You are considered disengaged and dismissible, perhaps even loathsome, if you have not acquired the unyielding, well-articulated opinions that are the offspring of certainty—opinions on everything from current events, to the nature of reality, to your own personal life. The zeitgeist asks us to grasp the ungraspable, to settle into a solid understanding of what’s right, real, and true, and to then clutch onto that view with a death grip, which could entail an actual fight to the death if you happen to meet someone who sees things differently. Which, of course, you will.

Walking, I began to see the absurdity of certainty, and that it doesn’t, in fact, exist. There is simply no knowing what will come next, whether you are walking across America or walking to your mailbox. I did not know where I would sleep until I was there, sleeping. I could not know the truth about anyone until I was actually with them, asking questions and listening. Which isn’t to say my mind wouldn’t try its best to create an illusion of certainty by assuming it could know something about someone simply by looking at them. This is one of the costs of an addiction to certainty: If you don’t know how to be in the openness of not knowing, you never get to find out who someone actually is, and you will, instead, relate to your imagined version of who they are, which is, in the end, yourself—your own judgments, assumptions, and projections.

I was astonished, even a little horrified, by the power of my addiction to certainty. One day in North Carolina, I came across a roadwork sign that read “Inmates Working.” I walked for two miles or so before encountering them, freaking out the whole way about what these bad men were going to do to me. When I came upon them, though, I saw that they were women, picking up trash. We ended up walking together for a while, and I listened.

“I’m getting out soon,” one said, “only three more years.”

“I’m getting out in a week,” another said. “First thing I’m going to do is see my kids.”

“First thing I’m going to do is just be alone. There’s fifty people to a room in prison. Ain’t no business of yours nobody doesn’t know.”

“People throw things at us out here, dirty underwear and bottles of piss. But I don’t give a shit because they don’t know me. They can judge me all day and I don’t care. I really don’t.”

When we reached the end of their road section, one of the women shook my hand.

“Careful out there,” she said, “not everyone’s as nice as us.”

As the states passed beneath my feet, I began to find liberation in the uncertainty, in choosing uncertain reality over the false and divisive certainties of my own mind. And on this journey of becoming human, off the road, is it any less important to know how to not know? Abiding in a state of I-don’t-know is an act of openness and therefore vulnerability. It is the beginning of humility, which, in turn, lays the foundation for real dialogue and deep encounter, which, together, house the work of understanding. And understanding is the host to that mysterious and sovereign visitor of the human experience: love.

Listening is I-don’t-know expressed as quiet action. It is not invested in a particular outcome, not attached to any agenda, not convinced of anything at all. It receives. It is ready to attend, to behold and to hold. To listen is to be for and with everything, even that which is against. It is not to condone immorality or to roll over in the face of injustice, but it is to refuse the violence of judgment and rejection, to stay wed to the practice of inclusion, even of that which cannot be understood. Understanding may come from listening, but it is not characterized by certainty and finality. You do not listen once and get the answer. The answer is constantly unfolding, and so listening must be practiced at all times. It is an apprenticeship from which there isn’t a single moment’s rest, although rest we must.

But let’s not rest for too long. When I set out to walk across America, I wanted to see each person as if they were living a story that the world needed to hear, that I needed to hear. I wanted to perceive them as a necessary and unique wellspring of experience that could, if approached with reverence, nourish life. I believe each of us longs to be listened to in this way, and that this longing festers if it is never recognized and met. So, who’s listening?

Andrew Forsthoefel is a speaker, peace activist, and the author of the book Walking to Listen: 4,000 Miles Across America, One Story at a Time. His narrative work has appeared on This American Life and The Moth, and he teaches walking and listening as practices in connective presence, personal transformation, and conflict resolution. He lives in Williamsburg, Massachusetts.